Conor Mark Jameson talks about William Henry Hudson as a Conservationist.

On May 19, 2022, author and environmentalist Conor Mark Jameson, gave a fascinating talk to The Anglo-Argentine Society on

William Henry Hudson, at the Argentine Ambassador’s Residence.

“W H Hudson, His Legacy for Nature in Argentina and the UK, was much enjoyed by those present.

In this follow-up article he explains the origin of his project to bring Hudson to life for more people, in a new book.

Finding W H Hudson

The writer who came to Britain from Argentina, to save the birds.

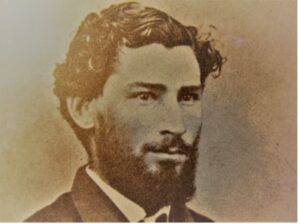

A life-size oil painting dominates the main meeting room at the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds’ (RSPB) base in a Victorian house in the heart of England: ‘the man above the fireplace’ – always present, rarely mentioned.

For most of the 25 years that I worked for the RSPB, at The Lodge, Sandy, Bedfordshire, W H Hudson looked back at me from that painting, pensive, and mute. I was always curious about this man, but it was only towards the end of my time there that I began a journey to rediscover and get to know him better.

A story told by Hudson in one of his books captured my imagination. He describes staying in a big house one night, sitting by a fireplace, as a storm raged. He fell asleep and had a nightmare, that when he died he would be stuffed by the taxidermists of hell, like so much of the wildlife he loved, and condemned to eternity with no voice. And it struck me that here he is today, beside a fireplace, voiceless – if no one is listening. I felt that he had more to tell us, some forgotten lessons from history, and my mission began to give him his voice back: a mission of restoration – stitching back together the faded tapestry of Hudson’s life, re-colouring it in places, and adding new threads from the lives of his closest friends.

In the forthcoming biography I have reconstructed the Hudson story through incidents mentioned in old letters and books. I aim to bring to life Hudson’s role as the only man in the room as Eliza Phillips, Emily Williamson and many other women founded his beloved ‘Bird Society’. I am especially interested in his kindred gaucho spirit ‘Don Roberto’ Cunninghame Graham, the celebrated ‘cowboy-dandy’ and the first socialist in Parliament. And I have also grown to love the fabled Ranee of Sarawak Margaret Brooke, hostess to many of the great names in art, music and literature of the era. And then there is Sir Edward Grey, Liberal statesman, and Nobel Prize-winning author John Galsworthy who, along with former US President Theodore Roosevelt, championed Hudson and helped him ‘break America.’ And I have also got to know better the tragic war poet Edward Thomas, who was, for Hudson, like the son he never had.

I have traced the unassuming field-naturalist’s path through a dramatic and turbulent era: from the moment of Hudson’s emigration to Britain from Argentina in 1874 to the unveiling by Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin of a monument and bird sanctuary in his honour, in the heart of Hyde Park, 50 years later. It was a place where the young immigrant had, for a time, slept rough.

By the end of his life, Hudson had Hollywood studios bidding for his work. He was a household name, in Britain and Argentina, and the Bird Society had at last reached the climax of a 30-year campaign, meeting with international colleagues in London to create the first global alliance of bird protectionists.

At its heart, my story aims to reveal Hudson’s influence on the creation of his beloved Bird Society by its founding women, and the rise of the conservation movement. I have tried to capture the strange magnetism of this mysterious man from the Pampas – unschooled, battle-scarred and penniless for a time – that made his achievements possible, and left such a profound impression on those who knew him. ‘I have known several men of genius, remarkable minds,’ said Edward Garnett, who advised many of the great and enduring names in literature, ‘but no man’s personality has ever fascinated me like Hudson’s.’

It seems that everyone wanted to keep the letters Hudson wrote to them – and he wrote a lotof letters. Hudson, meanwhile, burned almost all of those he received, and is said to have requested that his friends do the same. In many cases they went against his apparent wishes, enabling us today to piece together the friend and colleague they so obviously loved, for all his ‘native lack of delicacy,’ and his complexity.

The more I have found out about Hudson, the more perplexed I have felt that he has been allowed to fade into obscurity. In an odd way, this has felt like tracing family. Hudson was contemporary with my grandfathers’ grandfathers. I don’t know much about them, or my great-great grandmothers, other than that they were essentially rural people, like so many others living through a time of displacement, from the land to the city, from the outdoors to the indoors, from Scotland to Ireland and Ireland to America, with all the loss and regret that accompanied those advances in civilisation, as well as the hope, and the optimism for a better future. I have recognised in Hudson what feel like family traits, and a kindred spirit in his love for wild nature, and his nomadism.

The Pampas origins of Hudson of course add a whole other dimension of intrigue. His young poet friend Edward Thomas captured it rather neatly: ‘W H Hudson began by doing an eccentric thing for an English naturalist. He was born in South America’. I love that he brings emigration full circle, via Ireland and the USA. He came back – to England – with many stories to tell. He made sense of Britain, in a way only the fresh perspective of ‘half-foreign’ senses could. He also dared to challenge its norms and sacred cows; not having – nor knowing – his place.

I have dedicated the book to the memory of Hudson and his friends, in particular the women who founded modern conservation campaigning; who turned wildlife from something to be owned and exhibited into something to be nurtured and protected. And to underdogs and chasers of lost causes, everywhere.

A century after Hudson’s death, this is an overdue portrait in words, and tribute to arguably our most significant – and today most neglected – writer-naturalist and campaigner.

Conor Mark Jameson

What they said about Hudson

‘He had unfailing sympathy with young and inexperienced workers, and gave them every encouragement. When I was young he helped me over many difficult places connected with my position as Honorary Secretary of the Society for the Protection of Birds. His influence was in a curious way both potent, and permanent.’ Etta Lemon

‘Hudson’s writing is like grass that the good God made to grow, and when it is there you cannot tell how it came.’ Joseph Conrad

‘Our quarrel, then, is not with the classics, and if we speak of quarrelling with Mr Wells, Mr Bennett, and Mr Galsworthy, it is partly that by the mere fact of their existence in the flesh their work has a living, breathing, everyday imperfection which bids us take what liberties with it we choose. But it is also true that, while we thank them for a thousand gifts, we reserve our unconditional gratitude for Mr Hardy, for Mr Conrad, and in a much lesser degree for the Mr Hudson of The Purple Land, Green Mansions, and Far Away and Long Ago.’ Virginia Woolf

‘There was no one – no writer – who did not acknowledge without question that Hudson was the greatest living writer of English … I have never heard a writer speak of him with anything but reverence that was given to no other human being. For as a writer he was a magician.’ Ford Madox Ford (formerly Hueffer)

‘I’m not one of you damned writers – I’m a naturalist from La Plata.’ W H Hudso

About the author

Conor Mark Jameson is the author of Silent Spring Revisited, Looking for the Goshawk, and Shrewdunnit: The Nature Files. He lives today in a forest clearing, in the heart of fenland.